10 AF (atrial fibrillation) facts

In this article we will provide 10 in depth facts about atrial fibrillation (AF). It is mainly for health professionals.

Key Points

- Definition: most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, characterised by an irregularly irregular heart rate

- Complications: stroke, heart failure, and other cardiovascular complications

- Treatment: includes rate control, rhythm control, and anticoagulation

- Management: should be tailored to the individual, considering the patient’s symptoms, comorbidities, and risk factors

- Cause and effect: think about the cause(s) and effect(s) of AF in each patient.

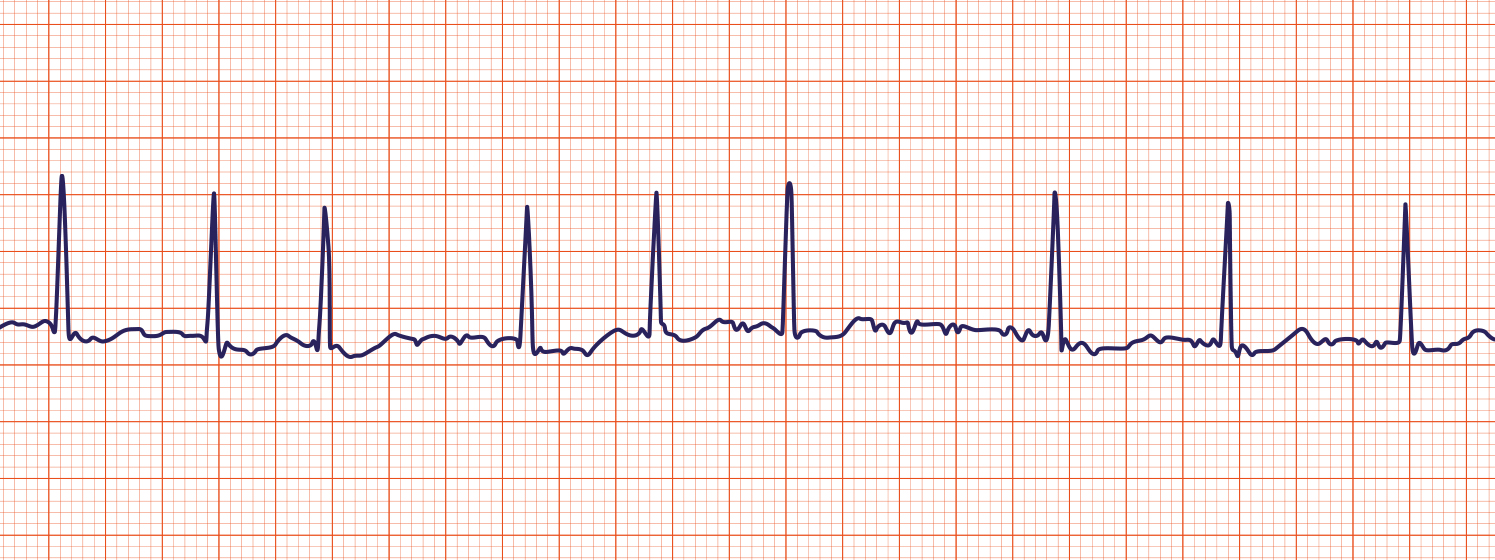

Typical AF on ECG

1. Definition

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia caused by disorganised electrical activity in the atria, leading to ineffective atrial contraction. It is characterised by an irregularly irregular pulse, and the absence of distinct P waves on an ECG. AF can be classified as:

- Paroxysmal: Intermittent episodes that terminate spontaneously within 7 days

- Persistent: Sustained beyond 7 days, or requiring intervention for termination

- Permanent: Long-standing AF where attempts to restore sinus rhythm have been unsuccessful or not pursued.

2. Epidemiology

- AF affects approximately 1–2% of the UK population, and its prevalence increases with age

- It is more common in men than women

- The incidence rises sharply in those over the age of 65, affecting about 10% of individuals over 80 years old

- AF is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality due to its association with stroke and heart failure.

3. Risk factors

- Age: Risk increases significantly with advancing age

- Hypertension: One of the most common predisposing factors

- Heart disease: Including heart failure, ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and valvular heart disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Obesity

- Hyperthyroidism

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

- Sleep apnoea syndrome

- Excessive alcohol intake (“holiday heart syndrome”)

- Family history: There is a genetic component in some cases.

4. Causes

- Cardiac causes: Hypertension, heart failure, valvular heart disease (especially mitral valve disease), ischaemic heart disease (IHD), cardiomyopathies, congenital heart disease

- Non-cardiac causes: Hyperthyroidism, acute infections (e.g. pneumonia), pulmonary embolism, excessive alcohol consumption, electrolyte imbalances, and surgical procedures (especially cardiac surgery).

Note 1. The ‘big three’ are mitral valve disease, ischaemic heart disease and hyperthyroidism. These need to be actively excluded

Note 2. ‘Lone AF‘ – also occurs. This is a phrase for AF when there is no obvious cause (especially cardiac).

5. Symptoms

- Palpitations: A common presenting symptom, often described as a rapid, irregular heart rate (in fast AF; slow AF also occurs)

- Fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance: Due to inefficient cardiac output

- Dyspnoea: Shortness of breath, particularly during exertion

- Dizziness or lightheadedness: Related to reduced cerebral perfusion

- Chest discomfort: May present as mild discomfort or more significant pain

- Asymptomatic: Some patients may be diagnosed incidentally during routine examination or screening.

6. Diagnosis

- History and examination: Look for an irregularly irregular pulse and symptoms such as palpitations or dyspnoea. Consider possible triggers, associated conditions, and family history.

Investigation

- ECG: The gold standard for diagnosis. Classic findings include the absence of P waves, irregular R-R intervals, and fibrillatory (f) waves

- Holter monitoring: Useful if paroxysmal AF is suspected, especially when symptoms are intermittent

- Echocardiogram: To assess underlying valvular and structural heart disease, left ventricular function, and left atrial size

- Blood tests: Full blood count, renal and liver function tests, thyroid function tests, and coagulation screen

- Chest x-ray: To rule out pulmonary causes of symptoms and assess heart size.

Differential diagnosis

- Atrial flutter: Often presents with a regular rhythm but can be irregular if there is variable conduction.

- Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)

- Ventricular ectopics or bigeminy

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT)

- Sinus tachycardia with frequent ectopic beats

7. Treatment

- Rate control: Manage symptoms by controlling the ventricular rate. First-line agents include beta-blockers (e.g. bisoprolol), calcium channel blockers (e.g. diltiazem), or digoxin (especially in patients with heart failure)

- Rhythm control: For patients with symptomatic AF where rate control is insufficient. Strategies include:

- Pharmacological cardioversion: E.g. amiodarone, flecainide (in those without structural heart disease)

- Electrical cardioversion

- Catheter ablation: Considered for those with symptomatic, recurrent AF despite medical therapy.

- Anticoagulation: Essential to reduce the risk of stroke. Use the CHA₂DS₂-VASc score to assess stroke risk and guide anticoagulation decisions. Options include:

- Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs): Apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, or edoxaban

- Warfarin: If DOACs are unsuitable (e.g. severe renal impairment)

- Lifestyle modifications: Addressing risk factors like hypertension, obesity, and alcohol intake.

8. Complications

- Stroke: Due to embolisation of thrombus from the left atrium. Stroke risk is increased fivefold in AF patients

- Heart failure: Can be precipitated or worsened by the arrhythmia

- Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy

- Increased mortality: Due to associated cardiovascular events.

9. Prognosis

- Prognosis depends on underlying causes, associated comorbidities, and adherence to treatment

- Effective rate and rhythm control, combined with appropriate anticoagulation, can significantly reduce the risk of complications and improve quality of life

- The risk of recurrence is high, particularly in persistent and permanent AF, and lifelong follow-up is often required.

10. Prevention

- Control of risk factors: Effective management of hypertension, diabetes, and other cardiovascular risk factors

- Lifestyle changes: Reducing alcohol consumption, smoking cessation, weight loss, and treating sleep apnoea can help reduce the risk of developing AF

- Early treatment: Identifying and treating reversible causes promptly (e.g. hyperthyroidism) may prevent the progression to sustained AF.

Summary

We have provided 10 in depth facts about atrial fibrillation (AF). We hope it has been helpful.

Top Tip

In a patient without cardiovascular compromise (controlled heart rate, no heart failure), treatment does not need to start immediately. It may be paroxysmal AF. Arrange to see them again soon in clinic and make a decision then, after a repeat examination.

Other resources

The rugby union great Alun Wyn Jones talks about his AF here.

MyHSN atrial fibrillation podcast (2024) – 11 min, 30 sec