10 chronic glomerulonephritis facts

In this article we will describe 10 facts about chronic glomerulonephritis (CGN).

5 Key Points

- Chronic glomerulonephritis is a group of autoimmune kidney disorders characterised by inflammation and damage to the glomeruli, which are tiny filtering units (sieves) within the kidneys. It can lead to progressive kidney damage and eventual kidney failure (ESRF).

- Types include IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). These conditions present with different mechanisms of kidney injury.

- Symptoms are very variable. They often include proteinuria, haematuria, hypertension, and those of AKI, CKD or nephrotic syndrome. However, it can also remain asymptomatic for long periods.

- Diagnosis requires a combination of: clinical assessment, urine tests (e.g. for proteinuria, haematuria), blood tests, and kidney biopsy (gold standard).

- Treatment is focused on managing symptoms, controlling blood pressure, addressing underlying causes, and immunosuppression in some patients. Early detection can significantly slow the progression to ESRF.

Let’s start with some basics first.

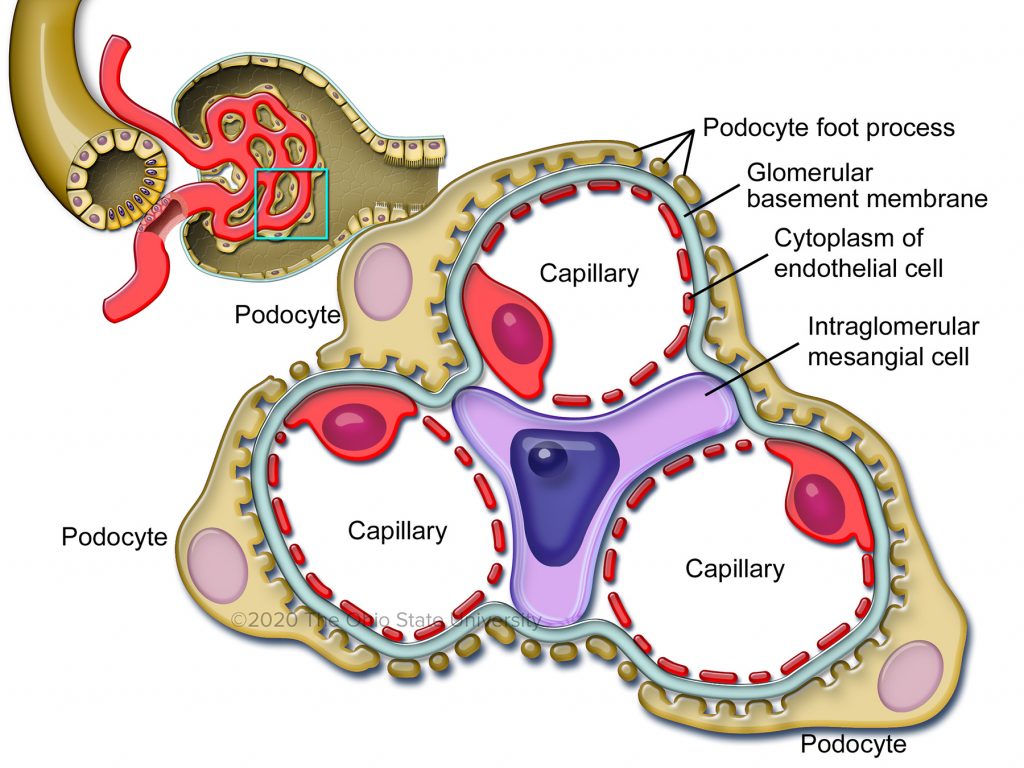

What is a glomerulus?

A glomerulus is a scrunched up ball of tiny blood vessels (called capillaries) – a bit like mini-worms – and is the tiny filter within the kidney. There are a million in each kidney. The blood is filtered through the sieve-like walls of the capillaries making urine. The glomerular basement membrane (GBM) is the middle wall (of three) of the capillary.

Diagrams of a normal glomerulus, and capillaries within it

Proteinuria (protein in the urine), ranging from low to very high, is the hallmark of GN. It is usually at least moderate, or high. It is a sign of damage to the GBM, i.e. the disease has made the GBM too leaky and protein is leaking through it.

1. Definition

Glomerulonephritis refers to a group of autoimmune diseases that involve inflammation of the glomeruli, which are the tiny filters within the kidneys responsible for filtering blood and removing waste products. Most are rare or very rare.

2. Epidemiology

Chronic glomerulonephritis can occur at any age but is most commonly diagnosed in adults aged 20-50 years. The incidence varies by geographical region and underlying risk factors.

In Western countries, IgA nephropathy is the most common form, while membranous nephropathy tends to be more common in middle-aged individuals.

In some regions, CGN may also be associated with certain infectious diseases, like malaria or HIV.

3. Types

There are two broad types of glomerulonephritis:

- Proteinuric. The proteinuria (protein in urine) usually ‘nephrotic range’, i.e, high or very high

- Minimal change disease (MCD) – the commonest GN in children. Usually presents as nephrotic syndrome, with normal renal function

- Membranous nephropathy. Also usually presents as nephrotic syndrome +/ CKD

- FSGS (focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis). Also usually presents as nephrotic syndrome +/ CKD. These patients can deteriorate quite rapidly.

- Less proteinuric. There is usually low-moderate level proteinuria. But there can be none

- IgA nephropathy – the commonest type of GN in adults. Usually presents as micro/macrohaematuria and loin/back pain – often in young adults. But can present as anything (AKI, CKD, proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome)

- Mesangiocapillary GN – usually presents as CKD; but can present in almost any renal way (like IgA nephropathy)

- Post-infectious GN – usually presents at nephritic syndrome (or AKI)

- Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN; or crescentic) GN – usually presents as AKI. Patients are usually very unwell. It can also be linked to epistaxes (nose bleeds) or haemoptysis (coughing up blood), as some types also have autoimmune damage to respiratory tissue.

Variable presentation

Although each type has unique characteristics and underlying causes, any one of the 7 types can (rarely) present in non-characteristic ways. For example, IgA nephropathy normally presents as micro/macrohaematuria and loin/back pain. But it can (unusually) present as nephrotic syndrome (like the 3 proteinuric GNs above) or acute kidney injury (AKI; rapid onset kidney failure) like RPGN.

4. Causes

Glomerulonephritis can be caused by various factors, including:

- Autoimmune disorders. These are of two types:

- Primary = arising in the kidney alone, e.g. minimal change disease (MCD, see below)

- Secondary = part of systemic (whole body) disease, e.g. like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Infections – including bacteria such as streptococci that cause Strep A throat and endocarditis (infection of a heart valve); and viruses like Hepatitis B and C, and HIV

- Certain medications – e.g. hydralazine. This is rare

- Certain cancers. This also rare

- Some forms of GN can be familial.

How these factors cause a GN is unclear. They somehow trigger an exaggerated (and sustained) response of the immune system to whatever is the original trigger.

5. Symptoms

The symptoms of GN are highly variable. They can range from no symptoms to:

- Rashes, and joint pain

- Haematuria (blood in the urine). This may be microhaematuria (blood that you cannot see) or macrohaematuria (that you can)

- Proteinuria (protein in the urine)

- Loin/back pain

- Swelling in legs (oedema) or shortness of breath – signs of fluid overload (i.e. signs of CKD or nephrotic syndrome)

- High blood pressure

- Decreased urine output in very severe cases.

6. Diagnosis

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of medical history and physical examination, urine and blood tests and a renal ultrasound. The ultrasound is done partly to check there are two kidneys (as a renal biopsy is likely to follow) and partly to exclude other diagnoses.

A battery of renal (kidney) immunological blood tests are also done. These can help with deciding which GN the patient has. But they are not reliable. They can be positive for diseases you don’t have, or negative for ones that you do.

This is why a kidney biopsy is almost always done, as a precise diagnosis is not possible without it. It also used to assess the extent of inflammation and damage – and chances of recovery.

Renal biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis of all types of glomerulonephritis.

A urinary ACR is important as it quantifies the level of proteinuria – that can be anything from normal to very high. It is not often normal.

Serological testing is also done, for conditions like HIV, Hepatitis B/C, or streptococcal infections.

Differential diagnosis

- Acute kidney injury (AKI) – usually look unwell. Most patients with CGN look well (ish), at least initially

- Nephrotic syndrome – of other aetiologies

- Polycystic kidney disease – usually little or no proteinuria

- Chronic interstitial nephritis / reflux nephropathy

- Renovascular disease (RVD) – usually low level proteinuria

- Chronic kidney disease of other causes (e.g. diabetic, obstructive or hypertensive nephropathy).

7. Treatment

Treatment for glomerulonephritis depends on the underlying cause and the severity of the condition. Some require no treatment.

Most require medication such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE, e.g. Ramipril) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs, e.g. Losartan) and/or SGLT2 inhibitors (e.g. Dapagliflozin) – which should be prescribed. These help to reduce the protein levels in the urine.

Diuretics (water tablets) may be required later, if the patient is fluid overloaded (shown by ankle swelling or shortness of breath, SOB).

Some types of GN need ‘special treatment’, with drugs and procedures to suppress the immune system. These include:

- Corticosteroids – e.g. methylprednisolone and prednisolone

- Cyclophosphamide

- Azathioprine and MMF (mycophenolate mofetil)

- Ciclosporin and tacrolimus

- Intravenous immunoglobulin

- Rituximab and other antibody treatments (called ‘biological agents’)

- Plasma exchange (similar to dialysis)

- Other treatments.

Some of these drugs are very strong and have significant side-effects. The decision to use (e.g. in the elderly) has to incorporate a risk:benefit assessment. In other words, it may be ‘safer’ not to use these drugs (or just use the weaker) ones, as the risk of side-effects outweighs the possible benefits. In severe cases, dialysis or kidney transplantation may be necessary.

8. Prognosis

The prognosis for glomerulonephritis is very variable. It depends on the specific type, severity and how early it’s diagnosed and treated. For example, MCD often resolves completely after.

Some forms of GN, especially FSGS, can recur in a transplant.

9. Prevention

Preventing glomerulonephritis is not easy, as it is a. a group of rare diseases, and b. has so many different causes. Some things can be done. For example, treating streptococcal infections promptly and effectively can help prevent post-infectious glomerulonephritis.

10. Complications

Without proper management, chronic glomerulonephritis can lead to serious complications such as:

- End-stage renal failure (ESRF): This is the final stage of kidney failure, requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation

- Cardiovascular events: Increased risk of heart attack, stroke, and other cardiovascular problems due to hypertension and kidney dysfunction

- Infections: Particularly in patients on immunosuppressive medication

- Electrolyte imbalance: Such as hyperkalemia and hyponatraemia.

If you suspect you have glomerulonephritis, it is vital to see a hospital kidney specialist (nephrologist) soon, to make an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan. Dialysis can be prevented, or the progression of kidney failure significantly slowed.

Summary

We have described what is chronic glomerulonephritis. We hope it has been helpful.

Other resources

There is more information on glomerulonephritis written by the renal team at UHCW in Coventry.