W – Wash your hands

I – Introduce yourself to the patient

P – Permission. Explain that you wish to perform an abdominal examination and obtain consent for the examination. Pain. Ask the patient if they are in any pain, and to tell you if they experience any during the examination

E – Expose the necessary parts of the patient. Ideally patients should be exposed from xiphisternum to pubis (classically they should be exposed from ‘nipples to knees’; but this is rarely done in modern practice to preserve patient dignity). Ensure adequate privacy

R – Reposition the patient. In this examination the patient should be lying flat with one pillow under the head, arms by the side. This is not possible with all patients so first check if they are comfortable in this position.

During the examination of the abdominal system a lot of information can be obtained by looking for peripheral signs of gastrointestinal disease. The examination is therefore split into a peripheral examination and then an examination of the abdomen.

End of the Bed

Hands

Looking for a liver flap

Face

Note. Have a quick look at the JVP (dehydration? liver failure?)

Inspection

First inspect abdomen from the end of the bed before closer inspection at bedside.

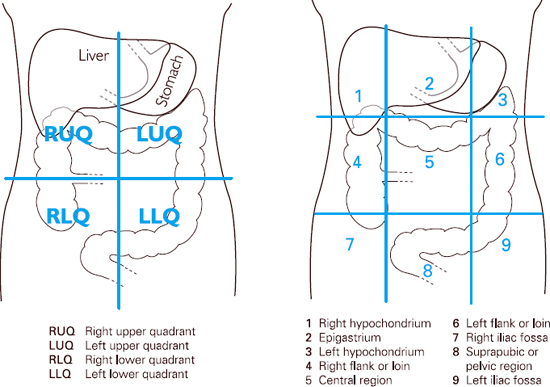

Initially look for general signs such as weight loss. Then check specifically for:

Palpation

Liver

A normal liver extends from 5th intercostal space to costal margin. It can be just palpable in some slim people (especially women).

Position your hand (low) in the right iliac fossa with fingers in an upward position facing the liver edge (alternatively you can use the radial aspect of your index finger). Press your fingertips inward and upward and hold this position while your patient takes a deep breath.

As the liver moves downward with inspiration the liver edge will be felt under fingertips. If no edge is felt repeat the procedure closer and closer to the costal margin until either the liver is felt or the rib is reached.

Spleen

The normal spleen cannot be felt and only becomes palpable when it has doubled in size. It enlarges from under the left costal margin towards the right iliac fossa

Position the palm of the left hand around the back and side of the lower rib cage.

The fingertips of right hand are then positioned obliquely across the abdomen pointing to the left costal margin towards the axilla (again, you may use the radial aspect of your index finger; as for the liver). Press your fingertips inward and upward and hold this position while your patient takes a deep breath.

Where to start and how to palpate the spleen

As the spleen moves with inspiration the edge may be felt under your fingertips. If no edge is felt repeat the procedure closer and closer to the left lower rib cage until the costal margin is reached.

If the spleen is not palpable, this procedure can then be repeated with the patient rolled onto right lateral position with knees drawn up to relax abdominal position. Palpate with your right hand while using your left hand to press forward on the patient’s left lower ribs from behind. It could be argued that this method should be used first, since very few patients have spleens which have enlarged to occupy the right iliac fossa.

Kidneys

The kidneys are retroperitoneal and posterior, so not usually palpable except in some slim people (right kidney more likely, as pushed down by the liver). Again they need to be twice as big as normal to be palpable.

To examine the left kidney, place the palm of the left hand posteriorly under left flank.

Palpating the left kidney

Position the middle three fingers of right hand below the left costal margin, lateral to the rectus muscle (opposite position of left hand). Ask patient to take deep breath and press both fingers firmly together. If the kidney is palpable it will be felt slipping between both fingers.

To examine the right kidney repeat the procedure with your left hand tucked behind the right loin and your right hand below the costal margin, lateral to the rectus muscle.

Palpating the right kidney

Bladder

Feel for the bladder as shown below, starting at the umbilicus and going down inferiorly.

Aorta

In thin patients’ or those with a dilated aorta, the aorta can be palpated by placing both hands on either side of the midline at a point half way between the xiphisternum and the umbilicus. Press your fingers posteriorly and slightly medially and the pulsation should be present against your fingertips. You are feeling for an aortic aneursym.

Palpating for the aorta

Percussion

Liver

Begin by establishing lower liver edge. Place hands parallel to the right costal margin starting at the same point as you began palpation. Repeat in a stepwise manner moving the fingers closer to the costal margin until the note becomes duller.

This is the position of the lower liver edge. Next find the upper margin of the liver. It can be located by detecting a change in note from the dullness of liver to resonance of lungs.

Spleen

Begin by percussing the ninth intercostal space anterior to the anterior axillary line (Traub’s space). If the spleen is not enlarged the sound will be tympanic. If it is dull continue to percuss in a stepwise manner moving hands towards right iliac fossa.

Note. Percussion of the spleen is rarely helpful in picking up a clinical sign (an enlarged spleen). Its a matter of going through the motions in an exam setting.

Ascites

If ascites is suspected percuss across patients abdomen (from midline to left flank) until the percussion note changes from tympanic to dull. Mark that spot and then ask your patient to turn onto their right side (if you are standing on right of patient).

After 30 seconds repeat percussing from the right flank towards the midline. If fluid is present it will have redistributed secondary to gravity; and therefore the area previously marked as sounding dull to percussion will now be tympanic.

Percussing for shifting dullness

Bladder

If the bladder is distended the suprapubic area will be dull rather than tympanic. Percuss from the level of the umbilicus, parallel to the pubic bone.

Auscultation

Bowel sounds

Place the diaphragm of your stethoscope on the mid-abdomen and listen for gurgling sounds. These normally occur every 5-10seconds however you listen for 30 seconds before concluding that they are absent.

Listening for bowel sounds

Absent bowel sounds indicates intestinal ileus. Increased bowel sounds indicate bowel obstruction.

Arterial bruits

Place diaphragm of stethoscope over aorta (in the epigastrium) and apply moderate pressure. If a systolic murmur is heard this indicates turbulent flow caused by atherosclerosis or an aneurysm.

Listen for renal bruits 2.5cm above and lateral to the umbilicus. They are rarely heard. Listen for femoral bruits. These are good surrogates for renal bruits (and therefore renovascular disease) and easier to hear than renal bruits. They also indicate the presence of peripheral vascular disease in general.

Palpate for ankle oedema (liver disease, or malnutrition).

The examiner may then say, “is there anything more you want to do?”

State that you would complete the examination by:

Finally explain to patient that your examination has been completed, thank them for their co-operation and help them to get dressed.

We have described how to examine the abdomen – and gastrointestinal system. We hope it has been helpful.

Abdominal examination (medistudents)

Guide to examination (UCL)

Review: Mealie, 2024