How to examine the kidneys – and urinary system

Urinary anatomy and physiology

Urinary tract

Urinary tract

The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs located on either side of the spine, just below the rib cage. They are about the size a palm: 12 (10-14) cm long, 6 cm wide and 3 cm deep, and weigh about 150g. The right kidney is slightly lower (and smaller), as it is pushed down by the liver.

Even though the kidneys only accounts for 0.5% of the body’s weight on average, they receive more blood (20% of the cardiac output) than all other organs except the liver.

The kidneys have 7 functions described here. It is important that a clinical assessment of the kidneys focuses on the anatomy of the whole urinary tract, and the cardiovascular system (CVS) that it interacts with, and all 7 functions.

Key Components

- Peripheral examination

- BP (BP, BP!)

- JVP

- Limited cardiorespiratory (with a focus on fluid state)

- Limited abdominal examination (with focus on kidneys, bladder and arterial bruits).

Introduction (“WIPER”)

- W – Wash your hands

- I – Introduce yourself to the patient

- P – Permission. Explain that you wish to perform a urinary examination and obtain consent for the examination. Pain. Ask the patient if they are in any pain, and to tell you if they experience any during the examination

- E – Expose the necessary parts of the patient. Ideally patients should be exposed down to the pubis. But this is rarely done in modern practice to preserve patient dignity. Ensure adequate privacy

- R – Reposition the patient. In this examination the patient should initially be sitting up (or at 45 degrees).

During the examination of the urinary system a lot of information can be obtained by looking for peripheral signs of urinary disease. The examination is therefore split into a peripheral examination and then an examination of the abdomen, kidneys and bladder.

Peripheral Examination

End of the Bed

- Look at the patient from the end of the bed for nutritional status, steroid facies (if on long-term corticosteroids), signs of easy bruising or scratch marks (CKD causes pruritus)

- Is there any sign of any obvious cause of renal disease (e.g. diabetes)?

- Are there any signs of a renal transplant, PD catheter, or AV (arteriovenous) fistula?

- Is there a nephrostomy tube(s): a catheter inserted through the flank into the renal pelvis enabling diversion of urinary drainage in the context of obstruction (e.g. secondary to malignancy).

Renal transplant scar

Renal transplant scar

AV fistula (for haemodialysis)

AV fistula (for haemodialysis)

PD catheter (and R renal transplant scar)

PD catheter (and R renal transplant scar)

- It is also important to look at the surrounding environment for sick bowls, food supplements, special dietary notices and fluid restrictions etc.

Bruising

- Bruising may be due to excessive corticosteroid use (e.g. immunosuppression in the context of renal transplant) or platelet dysfunction secondary to uraemia.

Skin lesions

- Inspect for obvious warts or skin cancers which can be associated with immunosuppression (e.g. renal transplant patients).

Hands

- Introduce yourself using a medical diagnostic handshake

- Examine the hands for clubbing, liver disease (e.g. palmar erythema, Dupuytren’s contracture).

Nails

- Look for signs of endocarditis (quite a common complication of tunnelled dialysis catheters) and vasculitis (nail fold infarcts, splinter haemorrhages).

Lindsay’s nails, a sign of CKD. It is distal reddish-brown band

Face

- Look for periorbital oedema (swelling around the eyes), common clinical feature of nephrotic syndrome. Inspect the conjunctiva for signs of anaemia

- Also look for xanthelasma and corneal arcus (hyperlipidaemia)

- Look at the mouth to assess dentition (endocarditis?) and presence of aphthous ulcers (SLE?)

- Gingival (gum) hypertrophy is caused by ciclosporin.

Blood pressure

This is a vital part of a urinary assessment for these reasons:

- Almost all patients with CKD have high blood pressure

- Accelerated hypertension causes CKD and AKI

- It is a marker of fluid state (low in hypovolaemia/dehydration, and high in hypervolaemia/fluid overload).

Jugular venous pulse

- The JVP is the most important sign in a urinary assessment, as it is the key marker of fluid state. You need to get very good at looking at the JVP. This takes years. But you might as well start today.

Examination of the chest (limited cardiorespiratory)

- Various renal diseases are associated with cardiac problems (and murmurs). So a brief auscultation of heart sounds is indicated in a urinary assessment

- For example, polycystic kidney disease (PCKD) is associated with mitral valve prolapse, and aortic regurgitation. Also endocarditis can present as an mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis.

- Even though it is not necessary to do a full cardiorespiratory examination, the following is part of a urinary assessment:

- Listen to the heart at left lower sternal edge, breathing forward in expiration. This will pick up most murmurs.

- Listen at the bases for bibasal crackles of fluid overload

- Feel the lower back for sacral oedema.

Examination of the abdomen

Inspection

- First inspect abdomen from the end of the bed before closer inspection at bedside

- Check specifically for:

- Renal transplant scar(s) and signs of haemodialysis (AV fistula or graft, or tunnelled dialysis catheter; or peritoneal dialysis (e.g. PD catheter)

- Abdominal distension (remember the 5Fs – flatus, faeces, foetus, fat, fluid)

- Herniae.

Palpation

- Position yourself by kneeling or sitting on the patient’s right hand side. Ensure your hands are warm. Ask patient if they have any pain or tenderness

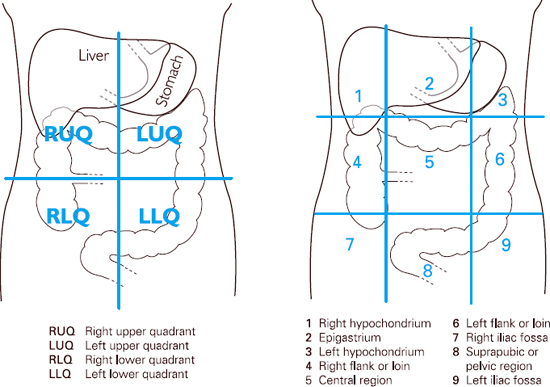

- Begin with light palpation of the nine segments (or 4 quadrants; see below). If patient has complained of pain begin at opposite side

- Observe patient’s face throughout palpation to ensure that you are not causing pain

- Light palpation is used to assess tenderness and guarding (a sign of irritation of the peritoneum)

- Proceed next to deep palpation of the same nine segments (or 4 quadrants). Deep palpation is used to assess for masses

- If appropriate, test for rebound tenderness (a sign of peritonitis)

Palpation of organs

Liver

- The liver is not normally palpable in most people with CKD and AKI

- In rare cases of PCKD, large cysts in the liver may make it palpable (occasionally a large liver is the only sign of PCKD, i.e. when kidneys are not palpable). This is one of the reasons you should examine for it in a urinary assessment

- A normal liver extends from 5th intercostal space to costal margin. It can be just palpable in some slim people (especially women)

- Position your hand (low) in the right iliac fossa with fingers in an upward position facing the liver edge (alternatively you can use the radial aspect of your index finger). Press your fingertips inward and upward and hold this position while your patient takes a deep breath.

Spleen

- The normal spleen cannot be felt and only becomes palpable when it has doubled in size. It enlarges from under the left costal margin towards the right iliac fossa

- The fingertips of right hand are then positioned obliquely across the abdomen pointing to the left costal margin towards the axilla (again, you may use the radial aspect of your index finger; as for the liver). Press your fingertips inward and upward and hold this position while your patient takes a deep breath.

Where to start and how to palpate the spleen

- As the spleen moves with inspiration the edge may be felt under your fingertips. If no edge is felt repeat the procedure closer and closer to the left lower rib cage until the costal margin is reached.

- If the spleen is not palpable, this procedure can then be repeated with the patient rolled onto right lateral position with knees drawn up to relax abdominal position.

Kidneys

- In most people with CKD and AKI, the kidneys are not palpable. Nonetheless you should obviously examine for them in a urinary assessment. In PCKD, both kidneys may be palpable, but they can be of normal (or slightly enlarged) size and so not palpable

- The kidneys are retroperitoneal and posterior, so not usually palpable except in some slim people (right kidney more likely, as pushed down by the liver). Again they need to be twice as big as normal to be palpable

- To examine the left kidney, place the palm of the left hand posteriorly under left flank.

Palpating the left kidney

- Position the middle three fingers of right hand below the left costal margin, lateral to the rectus muscle (opposite position of left hand). Ask patient to take deep breath and press both fingers firmly together. If the kidney is palpable it will be felt slipping between both fingers

- To examine the right kidney repeat the procedure with your left hand tucked behind the right loin and your right hand below the costal margin, lateral to the rectus muscle.

Palpating the right kidney

Bladder

- Feel for the bladder as shown below, starting at the umbilicus and going down inferiorly.

- If you suspect a bladder, obstructive nephropathy is a possibility, and the patient needs a rapid renal and bladder ultrasound.

Aorta

- In thin patients’ or those with a dilated aorta, the aorta can be palpated by placing both hands on either side of the midline at a point half way between the xiphisternum and the umbilicus

- Press your fingers posteriorly and slightly medially and the pulsation should be present against your fingertips. You are feeling for an aortic aneursym.

Palpating for the aorta

Percussion

Bladder

- If the bladder is distended the suprapubic area will be dull rather than tympanic. Percuss from the level of the umbilicus, parallel to the pubic bone.

Auscultation

Bowel sounds

- Place the diaphragm of your stethoscope on the mid-abdomen and listen for gurgling sounds. These normally occur every 5-10 seconds however you listen for 30 seconds before concluding that they are absent.

Listening for bowel sounds

- Absent bowel sounds indicates intestinal ileus. Increased bowel sounds indicate bowel obstruction.

Arterial bruits

- Place diaphragm of stethoscope over aorta (in the epigastrium) and apply moderate pressure. If a systolic murmur is heard this indicates turbulent flow caused by atherosclerosis or an aneurysm

- Listen for renal bruits 2.5cm above and lateral to the umbilicus. They are rarely heard. Listen for femoral bruits. These are good surrogates for renal bruits (and therefore renovascular disease) and easier to hear than renal bruits. They also indicate the presence of peripheral vascular disease in general.

Finishing off

- Palpate for ankle oedema (fluid overload or nephrotic syndrome)

- The examiner may then say, “is there anything more you want to do?” State that you would complete the examination by:

- Examining the hernial orifices (HOs)

- Examining the external genitalia, and performing a rectal (PR, to assess the prostate) and vaginal examination

- Fundoscopy (for any evidence diabetic or hypertensive retinopathy)

- Performing a urinary dipstick.

Finally explain to patient that your examination has been completed, thank them for their co-operation and help them to get dressed.

Summary

We have explained how to examine the kidneys – and urinary system. We hope it has been helpful.